Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

SCOTUS AND GERRYMANDERING

LIKE PONTIUS PILATE, CHIEF JUSTICE JOHN G. ROBERTS has washed his hands on a matter affecting humanity. As described by David Daley in “Trump Isn’t the Only One to Blame for the Gerrymander Mess,” The New York Times, August 13, 2025, “Over several years of rulings, this court has effectively rolled back laws that had for generations protected the right to vote.”

Image by Sarah Silbiger/Reuters from The New York Times.

Here are tidbits gleaned from Daley’s Guest Essay and related sources.

Bleeding the Voting Rights Act. Daley recounts, “Since he joined Ronald Reagan’s Justice Department in 1981 as a young foot soldier in the nascent conservative legal movement, Chief Justice Roberts has pursued the patient, steady bleeding of the Voting Rights Act. In 2013, he wrote the 5-to-4 decision in Shelby County v. Holder that effectively ended preclearance, the Voting Rights Act’s most effective enforcement mechanism, and liberated states, many clustered in the South, from federal oversight of legislative maps.”

“But,” Daley continues, “the case that did the most to bring us to our current impasse came six years later, Rucho v. Common Cause.… In that decision—also 5 to 4 and written by the chief justice—the court ruled that partisan gerrymandering is a nonjusticiable political question and shuttered the federal courts to future claims.”

Talk about washing one’s hands of guilt.

Traditional Gerrymandering Versus A.I. Daley continues, “His decision feigned ignorance of the difference between a gerrymander drawn in 1981 and one sketched out on sophisticated supercomputers four decades later. He pretended that voters can fix gerrymandering by tossing rascals out of office, a remedy that doesn’t take into account how gerrymandering works.”

Background. SimanaitisSays hasn’t shied away from the topic of gerrymandering. See “On Gerrymandering,” “Humpty Dumpty—Linguist Extraordinaire,” and my favorite two examples of gerrymandering.

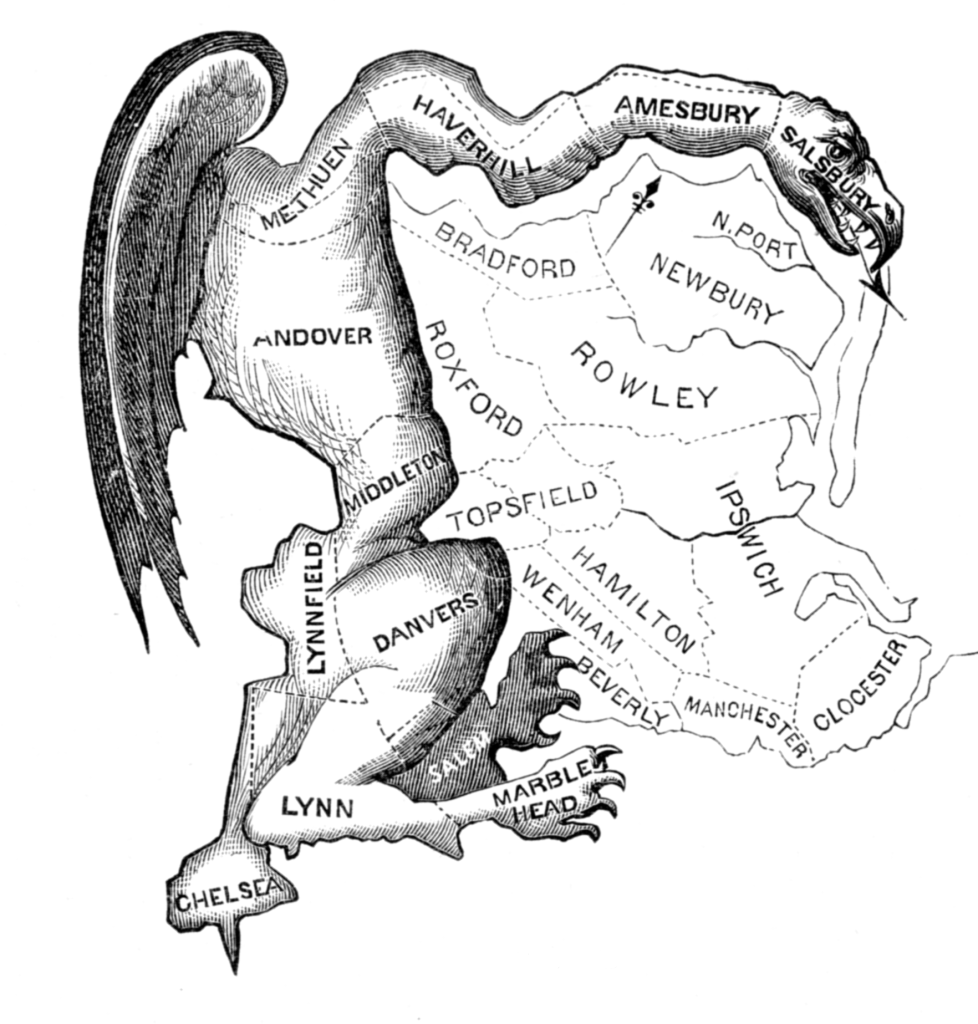

Above, the term “Gerry-mander” first appeared in the Boston Gazette, March 26, 1812. This image by Elkanah Tisdale. Below, the North Carolina 12th Congressional District that was court-ordered dismantled in 2017.

It was said of North Carolina’s 12th, “If you drove down the interstate with both doors open, you’d kill most of the people in the district.” Most of whom, by the way, were African-American Democrats.

These days, a corrected North Carolina’s 12th is roughly a square centered on Charlotte, and is much less focused racially, albeit still predominately Democratic.

SimanaitisSays noted, “On June 27, 2019, in a 5-4 decision the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that extreme partisan gerrymandering is still unconstitutional, but it’s up to Congress and state legislative bodies to resolve the problem.”

“Don’t wait up nights,” SimanaitisSays advised in 2020.

Alas, Currently. “In Election Cases, Supreme Court Keeps Removing Guardrails,” The New York Times, August 10, 2025, Adam Liptak cites Pamela Karlan, a law professor at Stanford and a former Justice Department official in Democratic administrations: She says, “We tell ourselves this story that every two years, voters go into the voting booth and pick their member of the House of Representatives. And right now it’s the other way around. The politicians are going into a room and picking their voters.”

Note, there’s nothing wrong in political partisanship—providing it’s informed voters who do the choosing.

Measuring Partisanship: the PVI: As described in Wikipedia, “The Cook Partisan Voting Index, abbreviated PVI or CPVI, is a measurement of how partisan a U.S. congressional district or U.S. state is. This partisanship is indicated as lean towards either the Republican Party or the Democratic Party, compared to the nation as a whole, based on how that district or state voted in the previous two presidential elections.”

Image from Wikipedia.

Wikipedia notes, “The Cook PVI is displayed as a letter, a plus sign, and a number, with the letter (either a D for Democratic or an R for Republican indicating the party that outperformed in the district and the number showing how many percentage points above the national average it received. In 2022, the formula was updated to weigh the most recent presidential election more heavily than the prior election.”

What’s more, Wikipedia also accesses PVI data for all 435 Congressional Districts. For example, Pennsylvania 3 (loosely, west Philadelphia) is an extreme with a rating of D+40. Alabama 4 (loosely, the State’s northern third) is another extreme at R+33. The current North Carolina 12, discussed above, rates a D+24.

PVI Data Fun. I reside in California 46 (D+11), part of Orange County jaggedly partitioned less along partisan lines so much as city jurisdictions. The two other OC Districts are California 45 (D+1) and California 47 (D+3).

You can access this array from Wikipedia.

You’re encouraged to check your own Congressional District’s PVI (and a look at the regularity/irregularity of its boundaries). Gerrymandered or not?

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2025